When I visited the LVF on a very hot day a few weeks ago, my objective was to see this exhibition, which has now moved on to Japan.

The exhibition presented the collection of the British entrepreneur and art patron Samuel Courtauld, which had not been shown in Paris for the past 60 years.

(Portrait de Samuel Courtauld © Courtauld Institute.)

“The Courtauld Collection: A Vision for Impressionism, brings together some 110 works, including 60 paintings and graphic pieces, which are mainly conserved in the Courtauld Gallery or in different international public and private collections. It features some of the greatest paintings from the end of the 19th century and from the very beginning of the 20th century.”

(excerpt from the exhibition catalogue).

Claude Monet, Automne à Argenteuil 1873.

So many Impressionist paintings have been reproduced on everyday products, I’m thinking of chocolate boxes, cards and posters, that it is one of the most widely recognized periods of modern art.

WHAT IS IMPRESSIONISM?

This is the definition of Impressionism from Wikipedia:

“Impressionism

is a 19th-century art movement characterized by relatively small, thin, yet visible brush strokes, open composition, emphasis on accurate depiction of light in its changing qualities, ordinary subject matter, inclusion of movement as a crucial element of human perception and experience, and unusual visual angles.

Impressionism originated with a group of Paris-based artists whose independent exhibitions brought them to prominence during the 1870s and 1880s.”

Claude Monet, Cap d’Antibes, 1888.

Today, exhibitions of Impressionist works are huge favourites with the public and the style is easy to love, with its wide range of colours and both bucolic and urban subject matters.

WAS IMPRESSIONISM A REVOLUTIONARY STYLE?

It is difficult for us to imagine that the contemporary audience and art critics were disgusted by the loose style that was revolutionary at the time.

Paris in the 1860s and 1870s, was that heart of the art world. The Academy of Fine Arts held annually the most important art world event of the time, the Salon de Paris.

For the Academy, good art meant realism imparted by close attention to detail, intricacy of composition, and a narrative that had its roots in the classical tradition. Being selected for the Salon would make or break an artists career.

In 1863, the Salon jury refused two thirds of the paintings presented, including the works of future masters Gustave Courbet, Édouard Manet, Camille Pissarro.

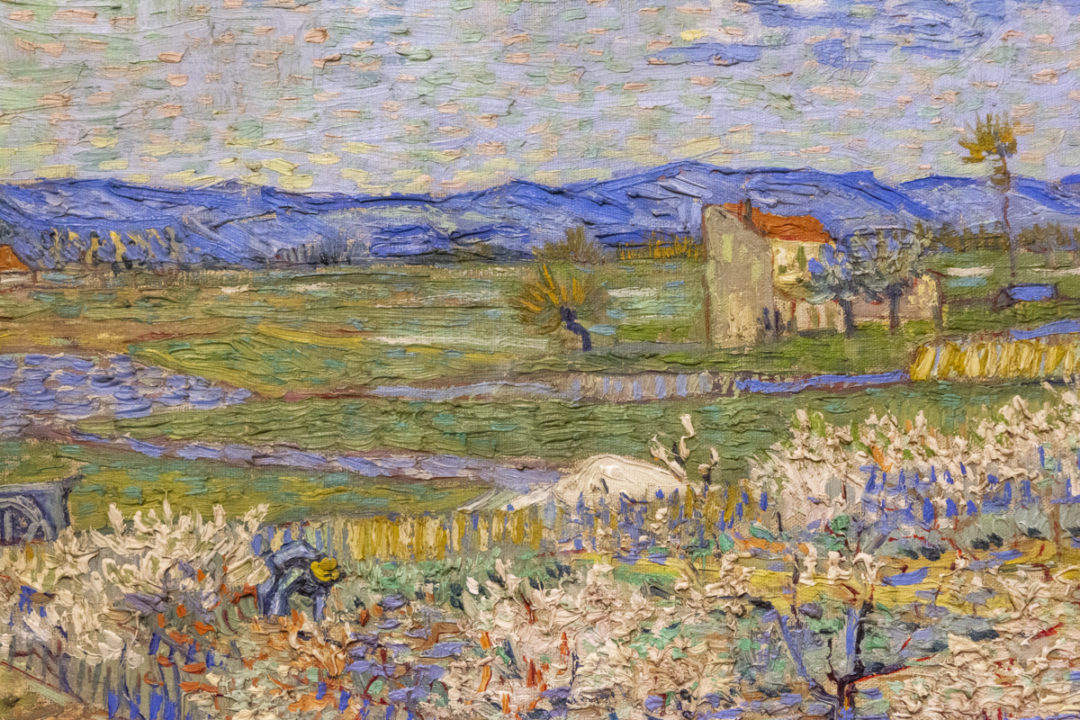

Vincent Van Gogh, Pêchers en Fleurs, 1889.

The rejected artists and their friends protested, and the protests were reported to Emperor Napoleon III. The Emperor’s tastes in art were traditional, but he was also sensitive to public opinion.

His office issued a statement:

“Numerous complaints have come to the Emperor on the subject of the works of art which were refused by the jury of the Exposition. His Majesty, wishing to let the public judge the legitimacy of these complaints, has decided that the works of art which were refused should be displayed in another part of the Palace.”

More than a thousand visitors a day visited the Salon des Refusés. The journalist Émile Zola reported that visitors pushed to get into the crowded galleries where the refused paintings were hung, and the rooms were full of the laughter of the spectators.

Details from Vincent Van Gogh, Pêchers en Fleurs, 1889.

Details from Georges Pierre Seurat, La Canal à Gravelines.

Critics and the public ridiculed the refusés, which included such now-famous paintings as Édouard Manet’s Déjeuner sur l’herbe.

Édouard Manet, Déjeuner sur l’herbe, 1863.

However, the critical attention garnered by the refusés also legitimized the emerging avant-garde in painting and the young artists successfully exhibited their works, outside the traditional Salon, beginning in 1874.

Claude Monet’s Impression, soleil levant.

The outraged art critic Louis Leroy wrote in his review that was printed in Le Charivari, on 25 April 1874,

“A preliminary drawing for a wallpaper pattern is more finished than this seascape,”

after looking at Claude Monet’s Impression, soleil levant, a sensory response to the Le Havre harbour at dawn.

The article was titled The Exhibition of the Impressionists , which was intended to ridicule Monet, but the term Impressionism was born!

WHO WAS SAMUEL COURTAULD?

Samuel Courtauld (1876–1947) was an English industrialist who is best remembered as an art collector. He founded the Courtauld Institute of Art and the Courtauld Gallery in London in 1932.

Samuel Courtauld’s links with France determined the spirit and motivations of his collection. His family, who originally came from the Île d’Oléron, an island off the Atlantic coast of France, emigrated to London in the late 17th century.

Having been silversmiths, his ancestors created a textile business in 1794, which became one of the largest in the world at the very beginning of the 20th century following the invention of viscose, a revolutionary synthetic fibre.

Samuel Courtauld became the company’s president in 1921, and would remain at its head until 1945. As a passionate Francophile, he regularly spent time in Paris, often purchasing works of art from French dealers, advised, amongst others, by the art historian and dealer Percy Moore Turner.

Samuel Courtauld played a fundamental role in the recognition of Paul Cézanne in the United Kingdom, by building up one of the greatest collections of the painter’s work.

His collection – built up in less than ten years between 1923 and 1929 with the help of his wife Elizabeth – was first shown in their neoclassical residence Home House, located in Portman Square in Central London.

Paul Gaugin, Nevermore, 1897.

Edgar Degas, Après la bain, Femme se séchant, 1895-1900.

In 1931, Samuel Courtauld’s created the Courtauld Institute of Art, housed at the time in the family residence of Home House. He wanted to give the public access to the history of art and to art works. He added seventy-four pieces, or half of his collection (paintings, drawings, prints), which were freely accessible to the students.

Elizabeth and Samuel Courtauld.

A Cézanne hanging in Home House.

The remainder of the collection, as well as several works which were acquired later on, was bequeathed to the Courtauld Institute upon his death.

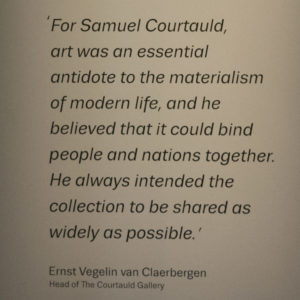

Samuel and Elizabeth Courtauld were visionary philanthropists, firstly because only seventy years after the inception of the movement, they recognized the vital place that the Impressionists hold in modern art. And secondly because they wanted to share their personal collection with the public and art students.

If you are interested you can find various publications about the collection here.

*****

If you are enjoying my articles, do please share this link https://henriericher.com/blog/

with your Francophile and art loving friends.

I would so love to share my passion for France, photography and art with more like minded people.

Thank you for visiting,

Henrie xo.